|

Part One

Albert knew he would be invisible

if he were very quiet,

soft as a spring rain;

for his father

was a muggy August night,

his mother a Sicilian tempest.

So Albert learned to move

Zen-like, the soles of his Puma's

barely rippling the surface,

his shadow faint and wispy.

Albert died as he lived,

silently and without leaving a trace.

Part Two

There was a time when

living was pretty intense

for Albert so he went

to see the parish priest.

The priest, a decent sort,

but unable to see Albert's

trembling shadow,

nor his imprisoned soul,

suggested a conference

with teachers and parents.

Albert thanked him and left.

He told me later that the people

were wrong about the priest;

he did have a sense of humor.

Part Three

I loved Albert,

a prince of a very different sort,

with strong feelings about what was right,

about what was fair. And this at a time

when the only things that were right

were what we were told.

One Saturday, as we were leaving

the Strand theater's afternoon feature,

the whoops and screams of the Indians,

and the whining heroic gunfire still

ringing in our ears, Albert began to cry.

He couldn't accept what had happened.

I told him it was just a movie,

and that he didn't understand;

besides we needed to do those things.

But Albert understood,

and with each heave of his waif-thin chest,

he apologized for all of us.

Part Four

Looking like preteen cherubs

we stood in the rectory

waiting for the start

or our third mass that morning.

Albert said he liked Buddhism much better

because it wasn't evangelical.

Where did he get these words?

I was still struggling with the Sunday comics.

He explained, and I had to agree.

It would be nice to belong someplace

where you weren't counted

or constantly being tested.

Part Five

Me and Albert grew up on the east side,

blue collar working stiffs, mostly Italians.

Lots of excitement there.

My father was a tough, wiry little guy,

a gandy dancer for the railroad,

and if you overlooked his regular

outbursts over politics, high prices,

and his ungrateful children,

was a rather nice guy.

While Albert's dad, a first class shoe maker,

was a big, loud, mean son of a bitch,

nice enough when sober, as the saying goes,

but he used to knock Albert around a bit.

I would tell my dad, and he would shrug;

tell me "you don't go messing

in other people's things."

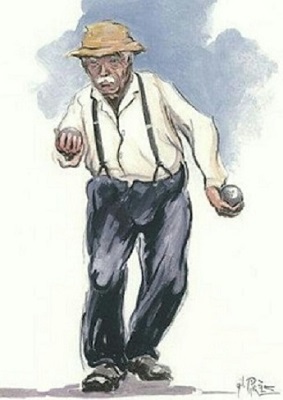

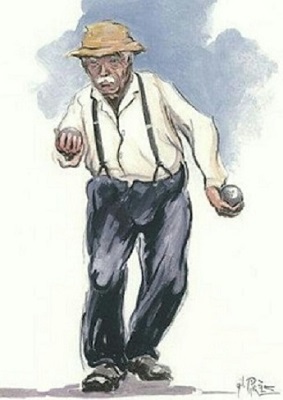

So one Saturday night, two weeks

into a vicious, juice sapping heatwave,

the old men were down at Yarusso's Café

drinking and playing bocce ball.

Albert's dad, upset with life I guess,

and flush with dago red, took issue

with how the game was going and kicked

over a wine laden table. In the resulting melee

old man Yarusso, wheezing through his broken nose,

barred all the active players from his café, which was akin

to the church excommunicating the unfaithful.

When the four black and whites finally arrived

there was no one around but a few peace

makers bending over Albert's dad lying

on the ground just beginning to stir after taking a hit

upside the head from a neatly thrown bocce ball.

My dad never mentioned the incident, as was his wont,

but as Albert pointed out to me,

he had a hell of an arm for such a skinny guy.

Part Six

While still a boy Albert ran his

father's shoe shop. I'd help him whenever I could,

sharpening skates, shining shoes,

and while Albert tap tapped, and cut and soled,

and I sharpened and cleaned and shined,

his father played dominoes

and drank red wine with his cronies

we called the Beaumont Street Gang.

He once told a bare bones story of

Machiavelli and then equated it to the president

and the government. Said in his casual way

that this war would never be won, and when

this president left the next one

would be the crook of crooks.

Some time later

while the nation mourned and moaned before

the nightly news, the Beaumont Street Gang

finally recognized the shoe shop prophet

by buying his father a quart bottle of anisette.

Albert just shrugged as he always did,

but I basked in his light.

Part Seven

When we were kids, me and Albert played

in his back yard where there was an old

beat up Ford squatting on blocks, with a small elm

tree growing through what was left of the canvas top.

Albert's father got a big kick out of that.

Beside the car stood an equally old pigeon coop

where his father, for many years, raised birds

for the table, until the city told him it was unhygienic,

and when their citations went unanswered,

raided the place in a crack house manner.

After his father had a stroke,

Albert found a pair of pigeons

who were in love and before long a flock

was circling the neighborhood again,

dropping droppings in its unruly way,

and the city was once again involved.

Albert just shrugged when questioned

said he thought they were racing pigeons.

His father, who was now just a shadow,

somehow showed Albert he was pleased

and suddenly it was just like old times.

Part Eight

Albert had a wonderful relationship with women.

His soft brown eyes and easy manner were enough

to keep him busy far past the time our teenage

hormones settled into a dull ache.

It was no surprise, I just couldn't figure it.

I was bigger, stronger, far more physical than he.

Could out scrap him, had more street smarts,

and once I learned the rules, could play

the game in a far more interesting way,

or so it seemed at the time.

But how I envied his aplomb,

his good-natured tolerance.

In one of the few times we talked about this,

he said, in an off hand way,

that maybe he was less needy than I.

It wasn't until years later that I realized

he was the most self contained person

I would ever know.

One expects a master's light to burn forever.

It was because he died so young

that I missed the connection.

Part Nine

Albert wrote the governor to protest

the treatment of penitentiary inmates.

Some time later he received a letter

from a prison functionary

thanking him for his concern,

and stating that everything possible

was being done to relieve the situation...

...and that they had already dismissed

two 'heads' and more changes

were in the works.

Albert commented that the lost 'heads'

would more than likely find

jobs within the federal system,

or even more likely,

with the military

because their punitory

training was invaluable.

Part Ten

I told Albert that I had blown a commitment

and because of a complicated timeline

wanted to know if I should trash the idea.

He asked me what I was afraid of?

Surprised, I puffed back -- 'nothing.'

The Buddha smile crossed his face.

If that's so, he grinned,

then the commitment should stand.

He was a prince, he was.

Part Eleven

Just before Albert left on his fatal trip,

he asked me to care for his dog Jilly

for a few days. Said he'd be back

on Tuesday, and I should watch her good

for she was depressed, wasn't eating well.

When Albert was late in coming back,

and just before I got the news that he wouldn't be,

she crawled under the back porch

and never again came out.

I didn't try to coax her or reason with her.

I figured she knew what she was doing.

Besides, I felt like crawling in with her.

Part Twelve

Albert left me a small piece of land

not far upstate; a few acres of bog

tucked back in a new growth forest.

Isolated, wonderfully frightening.

A wooden shack squatted

on the end of the car wide ridge

that snaked through the endless fog.

Melancholia hung like magnolia.

I went there when the days

began to run together,

tried to find that center.

And funny thing, I seldom felt the change

but I always felt his intent.

Epilogue

I had a dream...

...that Albert flew in from the Sudan.

He appeared strong and fit,

in spite of the horrors of the trip;

and he said nothing.

We hung around the corner for a time.

It was good just to be near him.

At the end,

he pressed lightly on that very sore spot,

I winched, then watched

as he collapsed in a heap,

disintegrated with a hissss,

his hat resting lightly atop his crumpled coat.

back

|